(Fwd by Bruce K. Gagnon on Aug. 22. Re-blog from the article of Counterpunch, Aug. 23 to 25, 2013 and Hollywood Progressive, Aug. 26, 2013)

K. J. Noh, Oliver Stone and Bruce Gagnon were on KPFA radio in Berkeley, California on Aug. 22 talking about Jeju Island and the horrors of the Navy base. See here.

Oliver Stone Visits Jeju Island

By K. J. Noh

In 1986, a young American director, burst out on the screens with a raw, charged, kinetic film. Depicting a country on the verge of popular revolution, it documents the rightwing terror and massacres that are instigated, aided and abetted by the US government. Beginning as the chronicle of a gonzo journalist on his last moral legs, the film starts out disjointed, chaotic, hyper-kinetic; the unmoored, fragmented consciousness of a hedonic drifter. As the events unfurl towards greater and greater violence, the clarity and steadiness of the camera increase, its moral vision clearer and fiercer, carrying the viewer through a journey of political awakening even as the story hurtles inexorably towards heartbreak, tragedy, and loss.

The name of the director was Oliver Stone. The film was “Salvador”. Opened to dismissal, derision and poor distribution, it nonetheless garnered two Oscar nominations , and is now lauded as one of the most important films of the period, acknowledged to have influenced the political debate, if not the policy, around Central America at the time.

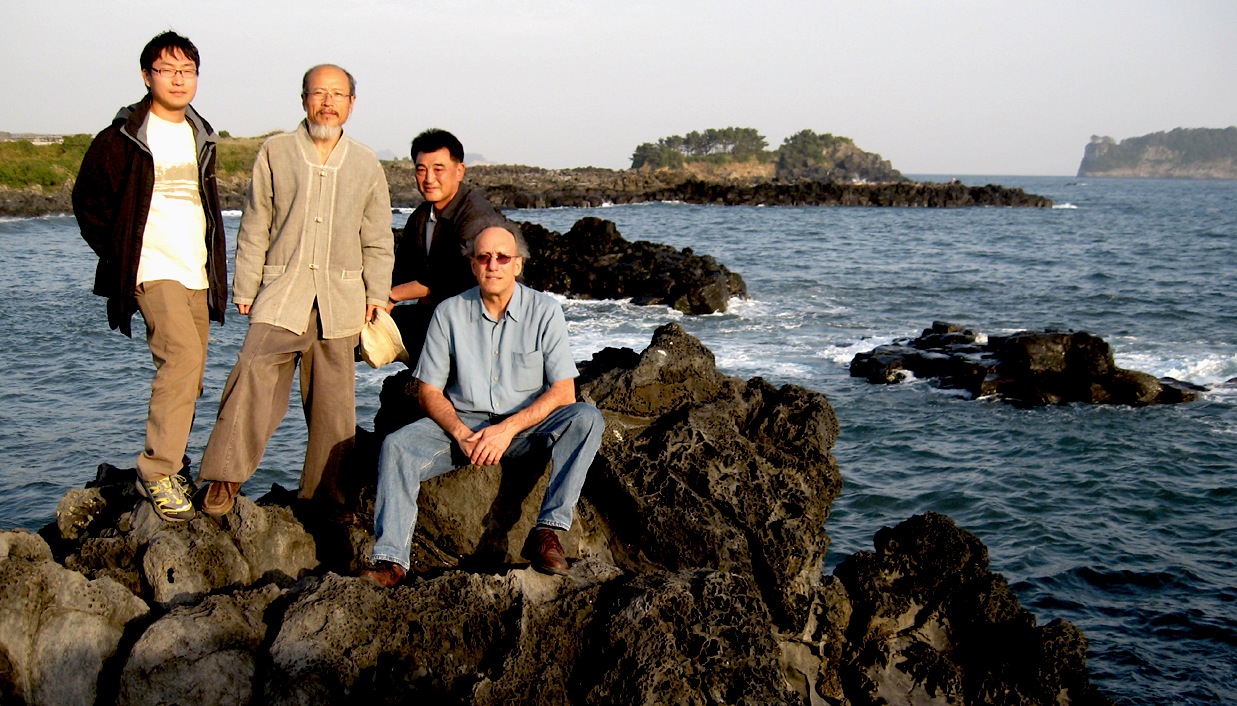

27 years later, Oliver Stone is discussing this film with the renowned Korean Film Critic Yang Yoon Mo. Professor Yang mentions Salvador, and the powerful effect it had on his generation during the violent, brutal military dictatorships of his era. “We loved it. It was a big inspiration to people all over the world. We obtained bootleg copies of it and watched it. It inspired a whole generation of young Korean film makers—for the courage and clarity of its vision. It was a model for us of what ethical and political cinema could be.” Stone smiles gently, and then reciprocates with his appreciation of current Korean Cinema—cinema that he himself may have had a hand in shaping—as he mentions “The President’s Last Bang”—a wry, understated morality tale about the assassination of the Dictator Park Chung Hee, during a dinner party-cum-orgy procured by his own intelligence services.

The rapport between two is warm and genuine and they talk as if they are old friends, old film buffs. It’s almost possible to forget for a moment that this is taking place inside a Korean Prison on Jeju Island, where Professor Yang has been sentenced to 18 months as a political prisoner, that he has been 70 days on a hunger strike, and that there are 6 of us crammed into a closet-sized visiting room: Oliver Stone, Father Moon, several activists, and an violent-looking police officer, whose every gesture and look intimates a furious desire to pound us into submission. On the other side, behind dual paned Plexiglas, the gentle Professor Yang is with another police officer, who is furiously transcribing every word that is exchanged.

It’s almost possible to forget that minutes before, we had been stripped of all cameras and recording equipment, had our ID’s confiscated and recorded, and had been escorted by half a dozen policemen to “have tea” with the chief of police, so he could “chat” with us. The police chief is warm and congenial, as only someone with absolute mastery of the rhetoric and machinery of power can be: Pontius Pilate, surrounded by his centurions, speaking softly to send the just the right mixture of benevolence and imminent threat. Out the window, to the left, we are surrounded by a panorama of verdant trees and hills. To the right, inches away, a squadron of blue suited, glaring police. It’s clear that there is more than one director in the room.

Professor Yang is being held in this jail for 18 months, along with dozens of other protestors, for the non-violent protest of a deep water Naval Base that is being constructed in Gang Jeong village on the Island of Jeju. He has been imprisoned 4 times.

****************************************************************

Jeju Island is a stunning subtropical island, 60 miles south of the Korean Peninsula, an ecological jewel that is home to UNESCO World Heritage sites, and biosphere reserves. World heritage sites are global treasures such as the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone Park, the Pyramids of Giza. Jeju has three of them. The shoreline of Gangjeong village, where the base is being built, is an absolute conservation area, made of soft coral, harboring many rare endangered species, and home to two thousand subsistence farmers and divers. The area called Gureombi is a site that is considered sacred to the villagers, a living, breathing landscape of tide pools, lava rock formations and stunning volcanic coastline irrigated with crystal clear springs:, the precious mineral kidneys of the island. Unfortunately, the Jeju base is also one of the centerpieces of Obama’s militaristic Pivot to Asia. Within easy striking distance—45 minutes by jet bomber, or 120 seconds as the missile flies–of Shanghai, Beijing, Tokyo, Taiwan, Vladivostok, it menaces all the major cities of East Asia. If we imagine the pacific table as a large family banquet, the military base is a loaded hair-trigger shotgun, and Jeju island is the rotating lazy susan platter in middle.

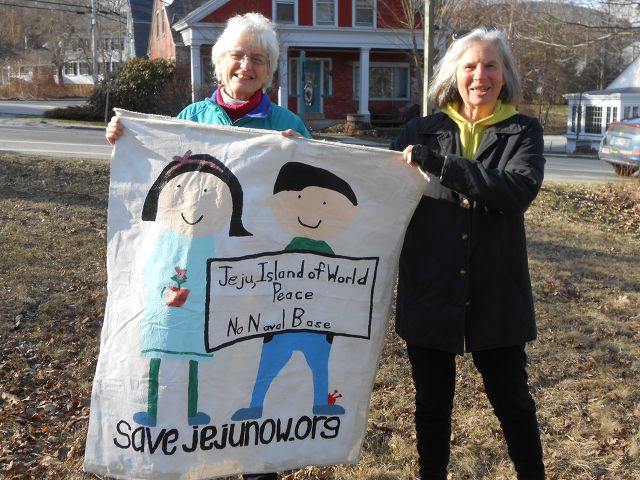

94% of the villagers are adamantly opposed to the construction. 140 National organizations, and 110 international organizations have called for its cessation. The Korean Parliament has demanded an investigation. The leaders of all the major religions in Korea have called for dialogue. The 5 opposition parties have challenged the legality of the construction. Yet construction has gone ahead, violating, subverting or ignoring every democratic process, every local, regional, national, international statute, charter and law. And so for 7 years, every single day, in one of the most disciplined non-violent struggles ever seen in the country, the villagers have been protesting the construction of this base with marches, prayers, petitions, art, masses, non-violent resistance . To date, 700 protestors have been arrested—including the largest mass arrest of Catholic Nuns in Korean History. Yang, along with other prominent intellectuals, civic and religious leaders, members of parliament, Buddhist nun, the Mayor of the village have all been “dragged like animals and beaten unconscious”, arrested, fined, sued, harassed by police, marines, and hired thugs; and received death threats. They have also been branded as Communists, opening them up to potential prosecution for Sedition under the draconian national security laws. It’s widely suspected Yang was singled out by the Korean National Intelligence Agency (the rebranded Korean CIA) in retaliation for drawing international attention to the issue. He is the longest serving prisoner to date.

****************************************************

Salvador is also an apt point of reference for Jeju: at the end of the war, Jeju itself experienced its own history akin to El Salvador, but on a scale—if such comparisons of human suffering are ever possible– that dwarfed the bloodbath in El Salvador: In El Salvador an estimated 75,000 were killed over 12 years, roughly 1-2% of the population, making it one of the bloodiest of the bloody, dirty wars in Central America. On the small island of Jeju, that number, or more, were killed in less than a year (10-30% of the population), making it the first, and bloodiest genocide of the post-war era, and the savage template for subsequent US interventions across the world.

The historical background is as follows: Korea had been a colony of Japan since 1910, suffering hideously under a brutal occupation. After the surrender of Japan in WWII, the US Military Government occupying South Korea was astonished to discover that there were thousands of functioning people’s collectives (worker’s committees)-forged from anti-colonial resistance– in the south, constituting a Defacto popular government, with strong nationalist and socialist leanings. In order to suppress this grassroots socialist government, the Korean People’s Republic,—American surveys show 80% of the population supported a socialist system—worker’s councils were outlawed, leaders imprisoned, a puppet dictator was rapidly installed, and the brutal apparatus of Japanese colonial rule was reconstituted in its entirety.

Jeju Island with its strong tradition of anti-colonial struggle was one of the strongholds of these indigenous collectives, leading it to be branded as a “red island” by the US Military Government. When popular protest against the division of the country, capitalist recolonization and the wholesale re-institution of the collaborator class and its police force became vocal, a scorched earth policy of genocidal proportions was unleashed. Using paramilitary death squads, strategic hamlets, free fire zones, mass rape, mass execution, torture, napalm, defoliation, entire villages were wiped out, 70-90% of all dwellings burned to the ground, and up to 80,000 massacred; these tactics were to foreshadow US policy across the rest of Korea, in South East Asia, Central and Latin America, Indonesia, Africa, and of course, El Salvador.

Members of Yang’s family were among the first killed in these massacres. For half a century in South Korea, it was a crime against National Security, punishable by imprisonment and torture, to breathe a word of this history. The island, a lush, beautiful subtropical paradise, with rich, volcanic soil, is strewn with unmarked mass graves, and haunted with unspeakable trauma. Those who survived these killing fields, fled in terror, some 40,000 or so. Those who remained were marked as subversives by family association, banned from civil employment, and driven into exile, poverty, suicide, madness. Even the massacres themselves were erased from history, leaving the survivors unable to mourn, grieve, or seek redress. After the slaughtered bodies were dumped into mass graves or caves, the facts vanished into an event horizon; even the memory of their obliteration was obliterated. Jeju Island, for all its beauty, is filled with ghosts—the unmourned dead, and the hushed, inconsolable pain of the survivors. In this context, a large portion of the population see the remilitarization of their Island—belatedly designated as an Island of Peace—as yet another desecration, the nightmarish continuation of an atrocity that has yet to end.

****************************

Oliver asks the Police Chief, about the conditions that prisoners like Yang are kept in: He asks whether they are able to exercise, read, receive and write letters. The Police chief, ever the congenial diplomat, answers, that he is extremely attentive to the health and well-being of his inmates, and that they are allowed all manner of comfort and recreation. He adds a comment about his concern about the hunger strike, and states with a worldly flourish, that “Esteemed Director Stone will find that the conditions of prisons in Korea are not that different from conditions in American prisons.” “Esteemed Director Stone”, does not seem assured, and without missing a beat, points out that “the conditions of US prisons are, according to the United Nations Rapporteur on Human Rights, some of the worst in the world. The systematic and routine use of prolonged isolation has been found tantamount to torture.” The police chief accedes than that perhaps there are differences, and with the hair-splitting skills of a trained bureaucrat, mentions that Korean inmates sleep on traditionally heated floors, whereas American prisoners must sleep on beds. There’s no easy conversion scale to weigh the tradition of intimidation, bastinado and torture of a Korean prison against the isolation, violence, racism of the American penal system. A beautiful police woman, impeccably coiffed, and immaculately made up,–a police geisha, if you will– passes around spring water in exquisite cut crystal glasses, with the terrifying precision of an assassin, moving, as if on cut-steel grooves. There is no need for ice. We gulp our water, thank the police chief, and Officer smash-your-face-in-if-you-so-much-as-blink-wrong then escorts us, with 5 other officers, down to the visiting rooms to meet with Professor Yang.

*************************

90 minutes earlier, Oliver had flown directly in from Barcelona, after 7 days non-stop night shooting of a commercial, and had landed in Jeju, exhausted and bleary eyed. “I don’t usually do commercials”, he says, “but this was soccer—it encourages people to exercise, get healthy, so I’m okay with this”. Oliver looks to be needing a bit of exercise himself: 10 time zones and 20 hours of non-stop flying and transit have left him exhausted and drained. He has wiped clear his schedule, and made a huge sacrifice to travel to Jeju, but as his exit from customs is delayed, the greeting team of local activists at the airport has become anxious that he will simply be denied entry into the country. The Korean government has already denied entry to several international peace activists at the airport—most notably Elliot Adams, Tarak Kauff and Mike Hastie from Veterans for Peace, and it is not inconceivable that they would do the same for any perceived rabble-rouser. Alternatively, they are not above a little “rough play”, and for the Korean Authorities, for whom a beatdown is just a friendly way of getting acquainted, a sound drubbing could be spun as just an over eager welcome or a misunderstood expression of solicitude. The burly men in suits and earpieces tailing the greeting team make this not an unlikely possibility. Finally, when Oliver is released from transit purgatory, all of us breathe a sigh of relief, although for some reason his luggage has gone AWOL. Over the next 48 hours, the luggage will be repeatedly located but yet somehow unrecoverable, claim documents will not be filed, others improvised, leading activists to wonder if this is part of the harassment: :disrupt morale by disrupting logistics, separate the “enemy” from their materiel—in this case, Oliver’s clothes, toiletries, medicines, and his colorfully subversive collection of bandannas.

After a frantic, truncated 30 minute lunch at a local restaurant—there are no power lunches in rural Korea, only hurried ones—the team belatedly shuttles to the prison, where Professor Yang is waiting. We submit to the mandarin ceremonies of power which permit us the short visit to professor Yang. Then, as Oliver and the professor are talking shop, Oliver mentions his new series, “The Untold History of the US”. As a director, he is known for his prolific output, sometimes making two or more films in a single year. “The Untold History”, however, is a 5 year labor of love, a meticulously researched ten hour documentary (and 700 page companion volume), unmasking and chronicling of the rise of US Imperialism. Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History of the United States” is most often mentioned in the same breath, but the other great chronicle of imperialism and its excess–Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War, is also an apt comparison: “The cause of all these evils was the lust for power, arising from greed and ambition, and from these passions, proceeded the violence”. Professor Yang seems intrigued, and although he has been incarcerated too long to have heard of it, he promises that he will try to find a way to see it. Oliver expresses his concerns for his well being, and inquires as to the depth of his support among other artists. Then all too quickly, visiting time is over, and we are reduced to silent gestures of good will and hope across the plexiglass. Professor Yang touches his palm to the glass, Oliver touches it, and then he slowly bows to each of the visiting team, hands together in traditional blessing. Professor Yang seems to have been deeply moved by the visit, but for us, it’s hard to avoid the sense of abandoning a comrade in prison. We stop as we are exiting the prison to do a quick interview with a wire agency, and Oliver fiercely denounces the detention of Professor Yang. “The courage of Professor Yang inspires me” he states, with fire in his voice. “I believe without a doubt that he is a prisoner of conscience and I call for him to bereleased immediately. I deplore the militarization of Jeju Island. I deplore the building of the base”. There is passion and heart in his voice. He will reprise this theme many times over the next few days, but like the other stories about Jeju, these statements will pass largely unreported in the mainstream press.

********************************************

Nothing in Korea happens in half measures, and the heat is no exception. The Jeju heat is swelteringly close to 100 F, the humidity is in the 80’s and although there is a march for peace against the military base that is happening—an epic two day march that will circle all the way around the island, then meet up in the north and come together for a mass rally at a civic plaza, followed on the next day, by a human chain around the base–we wonder if after the harassment, delays, power plays, exhaustion, the blast furnace of summer heat is too much. We ask Oliver if he is up to joining the march, as planned.

Oliver is still resolute. “Let’s do it” he says.

The following day, Koh Gil-Jun, a key protest organizer and artist–one of the key visionaries of the museum on the Jeju Massacre–will fall to the ground during the march, vomiting, paralyzed; done in from heat, stress, exhaustion, harassment, pain. He will be taken to emergency and diagnosed with a hemorrhaged vessel in his brain. But no one seems to be measuring risk against commitment.

“Haegun giji, gyolsa bandae!”

We arrive at the march—an ocean of yellow shirts and banners, youth, children, men and women, internationals—and a huge roar goes up, the tide of people surges and vibrates with energy. If, as it has been said, the true spiritual quest is not upward, or even inward, but forward, to march forward, surely this is one of its greater manifestations.

“Haegun giji, gyolsa bandae!”

A thousand banners flutter in the wind, and the crowd is abuzz with excitement and passion. Chants thunder through the streets, like an unstoppable heartbeat. Like the huge people’s marches that toppled the previous dictatorship, the winds of history, the breath of solidarity, the tide of inevitability, seem to propel the marchers upwards, onwards, forwards.

“Haegun giji, gyolsa bandae!”

Every dimension of human aspiration is present and alive.

Drenched in sweat, Oliver puts on a yellow T-shirt on top of his sweat-soaked shirt, and is invited to join the march at the front. He modestly declines to walk “point”, and falls into the ranks. Fabled director, Hollywood icon, decorated war veteran, becomes just another marcher in a sea of protestors, a forest of banners, marching, this time, against the Imperium.

“Haegun giji, gyolsa bandae!”

“Oppose to the Death, this Naval Base”

*******************************

.

“How do we stop this thing? How do we stop it? We have to stop this thing.” He asks, as we return later to his lodgings. We tell him that it already has stopped, –temporarily—construction that has been ongoing nonstop, 24 hour a day, Christmas, New Years, holidays, has suddenly tapered off, and the site is eerily silent, except for the occasional pile driver. “It’s gone silent in your honor”, we joke. “You should move here permanently”.

Oliver looks out at the coast line from the balcony of his modest B & B. From there, what was one of the most stunning vistas on the coast, you can see a shoreline littered with rubble, construction cranes, bull dozers and concrete jacks.

Earlier in the day, passing the lego-block apartment complexes that were sprouting near the main city, he had jokingly inquired if they were Soviet-inspired. “This is as cheesy as anything Donald Trump would build. Donald Trump would love it here. How does a country with such good film makers have such bad architects?” He had quipped.

But looking out over the construction, no one feels like joking.

It’s not just narcissistic bad taste.

It looks evil.

**************************

Afterwards, we head out to the docks, to take a boat tour of the coastline. Mindful of his reputation and activism, Korean news media has largely honored his visit by coordinated and conspicuous neglect, but Oliver has had the foresight to pull in a Japanese news crew. A camera crew from NHK meets us at the docks, and we get onto the boats, and start our own tour of the coast line. Out in the water, with the cool breezes, the heat abates, and it’s hard not to get a sense of the enormity of it all, the power, the endless beauty, the endless generosity and abundance of this area. The pacific Islanders have a term, Moana Nui, which sees all the pacific peoples living in a harmonious web of mutual co-existence and nourishment, connected by the benevolent ocean. Connect all, so we may all live. There’s enough for all of us: ocean, space, energy, love.

It’s hard to reconcile this with the realpolitik that is gridding off this area as a deadly chess game: control the center of the game board–Jeju Island–the king pawn/queen pawn squares, dominate the vectors and channels of lethal force, subjugate all enemies: Occupy so we may dominate and kill.

The gentle swaying and cool breezes allow us to wash off some of the day’s earlier struggles, and we find the tour both relaxing and exhilarating. The ocean is a deep, sparkling cobalt, and with its gentle billows and power, we feel again the enchanting power and beauty of the water and the island.

On the boat as our tour guide, is a Jeju local, a shaman, meditation teacher, and also, incidentally, the founder of the first and only battered woman’s shelter on the island. “Domestic violence is inseparable from State violence” she tells me. “Militarism and military violence filter down into the smallest recesses of family life. We can’t struggle against domestic violence without challenging this base.”

She tells us about the origin myths of the island, the goddess resting her head at the peak of Mt. Halla, the volcanic peak of the Island, with her feet pointing up to become the island. The creation myths of Jeju island are all goddess myths, what powers lie within and around this island are nourished and channelled from the energies of the feminine.

The feminine is most clearly represented by the Haenyo, the legendary women divers of Jeju Island. The shaman’s mother was such a Haenyo. Fable has it that some travelled to the Japanese Isles, millennia ago, taught the Ama diver women of Japan and then spread the skill spread across the pacific; whether this is true, is unconfirmable, but what’s clear is that this is one of the few places on the world where breath-holding subsistence divers still exist. If the Haenyo have survived to this day, it is clearly because these women are a force of nature: they start diving in childhood, and continue diving into their 80’s and 90’s. They have the courage, endurance, and diving skills to make sissy boys of the Navy Seals’ Underwater Demolition Teams, and during the 1930’s, they spearheaded the resistance to the Japanese Military Occupation on the island. They spend hours in the water, three minutes with each dive, through all seasons, surrendering their lives to the ocean. Their hemp or twilled cotton shirts have been replaced by modern wetsuits, but that is the only concession that they have made to technology. They steadfastly refuse to use scuba gear, or even snorkels, relying on traditional practices of breath control, prayer, and meditation, both as part of tradition, but also with the understanding that stripping the sea bed with technology is pointless stupidity. Their lifestyle is profoundly spiritual and ecological, and it is dying out in the area. The base construction will be the death blow.

Centered around the economy of the Haenyo, Jeju island has, for centuries, been a traditional matriarchal society. “No thieves, no beggars, no gates”, was a phrase commonly used to describe the society of Jeju island, cooperative, communal, matrifocal, an indigenous form of socialism that led itself naturally to the grassroots workers’ councils that flourished after the liberation from the Japanese. These worker’s councils were the basis of the “red island” designation by the US Military Government, and were the trigger for the genocide. Bases will finish off what death squads, napalm, free-fire zones, and killing fields could not. If and when the base is completed, the traditions of generations of powerful women will be replaced with bar girls, prostitutes and housemaids. A young girl who would have learned from her grandmother to read the tides, dive to a hundred feet with only the air in her lungs, and talk to the spirits of the ocean to face down death, will be servicing GI’s on her knees in back alleys. Cultural Genocide, if the term has any meaning, seems appropriate here.

Basalt Columns appear on the Island that we are passing. This is Beom Seom, “Tiger Island”, a Unesco Reserve, and at close range, you can see the entire island is formed from hexagonal basalt columns, like a dark, chiseled, striated jewel in the ocean. The top of the high cliffs is covered with pine trees, and there are wave-carved tunnels and archways around the island, an exalted, mystical architecture. Whether you believe the myth of the goddess’s feet poking out of the dark sea or some other supernatural explanation, you know that you are at the conjunction of extraordinary forces of nature. Underneath the billowing ocean, there is soft coral, and in front of us, the volcanic peak of Mt Halla, and all around us, the breeze and endless ocean.

Turning the corner of the island, we witness full on the devastation of the base construction.

We stop the boat.

From the ocean, we can see the entire scale of the violation. It is monstrous.

“F***” Stone blurts out. .

Do not touch a single pebble, a twig, a flower. All of it is sacred, the protestors have been shouting for years.

7 story, 10,000 ton, steel-bladed caissons, have been sunk into the soft coral below, exposing themselves above the waterline like the bared fangs of a mad predator. Construction has blasted, pulverized, and befouled the sacred Gureombi, the living kidneys of the island, paved it over with concrete, leaving it looking like a massive latrine. Pile drivers, bull dozers, cranes, high explosives have gashed the womb of the Goddess of Mt. Halla, leaving concrete and steel maggots writhing out of its innards, and bleeding dark silt and slurry into the pristine ocean.

Around the crime scene, a sanitary cordon of buoys and construction curtains.

It is the scene of a heinous rape-murder.

Oliver gets up on the edge of the boat. Part lecture, part possession, part jeremiad, he points to the shoreline and launches into a full blown soliloquy.

“This base will host US destroyers, aircraft carriers, Aegis missile batteries, nuclear submarines. It’s part of Obama’s pacific pivot, a chain of offensive bases from Myamar, Phillipines, Thailand, Korea, Okinawa, a necklace of bases to choke off the pacific. It’s being put in place to threaten China. Even as we speak, war materiel is being shifted from Iraq, Afghanistan to the pacific”.

“We have to stop this. All this is leading up to a war, and I’ve seen war in Asia.” His voice trembles. “I do not want another war here. I’ve seen war in Asia, and we cannot have another war here. We have to stop this thing”.

He turns to the Shaman, invites her to put a hex on the base, to invoke Gods higher than those of empire, profit and militarism. .

Oliver then gestures himself, hurling passion, heart, grief, onto the shoreline.

We all scatter our prayers, curses, tears, to the waves and the setting sun.

Everyone is silent, as we head back to the shore.

“It is a given that those who would struggle for peace, must first know the meaning of devastation”.

– By K. J. Noh who is a long-time activist and member of Veterans For Peace

Global Network Against Weapons & Nuclear Power in Space

PO Box 652

Brunswick, ME 04011

(207) 443-9502

globalnet@mindspring.com

www.space4peace.org

http://space4peace.blogspot.com/ (blog)